Specialized Gear, Clothing, Health and Food Advice for Hiking in Tajikistan’s Mountains

Specialized Gear, Clothing, Health and Food Advice for Hiking in Tajikistan’s Mountains

This article assumes that you already know what you are doing in terms of gear, equipment and clothing selection for mountain travel. The purpose of this article is to help you adapt that knowledge to some unique circumstances in the mountains of Tajikistan, particularly on longer treks in isolated areas. Some of the advice below is not for people doing a few days at mid-altitude, but most of the information provided applies to a range of trips, from short and light to long and heavy.

Tajikistan’s mountains have some characteristics that may not be familiar to some hikers, and that should affect your gear and food selection:

Big elevation differences. Trailheads can be as low as 1200 meters, with the highest hike-able passes being over 5000 meters. This equals great temperature and weather differences, with chance of heat exhaustion at lower elevations, and hypothermia at the higher elevations, all within the same summer month.

Outside of a few popular hikes, there is total isolation once you go above the highest shepherd camps (no locals, no tourists).

Very few opportunities to resupply on food, and a meagre selection when you do.

The trails are very rough, or a route may follow a non-existent trail over open terrain.

Social norms in many mountain regions affect what you should and shouldn’t wear.

Many stream and river crossings with no bridges on some routes.

High passes may have snow fields or cornices that don’t melt in the summer, some have glaciers – even on trekking routes.

And, more recently, very unpredictable weather versus the more stable summer patterns previously seen in the mountains here.

If the list above sound intimidating or worrying to you, don’t worry. You can find much easier/safer conditions in the popular hiking routes of the Fann Mountains and on a few of the popular routes in the Pamirs (Jizev, Marx & Engels Peak Meadow, etc.). Or hire a guide.

Note: the brands below are very USA/Canada-centric. There are probably easier and cheaper options if you are in Europe, Asia, etc. Use the brands and models I mention to find the equivalent brand/model that is available in your country.

Shelter and sleep system

Tent: Guesthouse to guesthouse trekking does not exist, as they are too far apart – you need the tent. Any highly rated 3-season free-standing tent or trekking pole tent will suffice (most of the time), but it must be a tent that can withstand alpine conditions. Make sure it’s a tent that does well in wind which you may get at higher altitudes or on a ridge (if you have no choice but to camp there). And get tent stakes that are designed for rough rocky ground. Something like the MSR Mini Groundhogs should work, but I’ve found that the occasional combination of loose ground (e.g., gravel), wind and the demands of a trekking pole tent call for wider stakes. So I have my four corners staked out with regular (longer/wider/bigger) MSR Groundhogs.

Non-freestanding tents that rely on trekking poles are increasingly popular - I own one. But two of their drawbacks — their large area footprint and the 100% need for at all 4 corners to be very securely staked in a perfect geometric shape — greatly limits the spots where you can pitch your tent, and the angles you set them up at. Tajikistan’s mountains have a shortage of soft and flat spots to camp. Also, these tents don’t do well when their broad side is facing the wind.

During my 4 months in Tajikistan’s mountains in 2023 I wished I could have switched mid-hike to a freestanding tent. It would have saved me lots of time that I spent searching for a decent spot and fighting my tent as I tried to pitch it on rough ground. But I have decided to stick with a trekking pole tent as I worry about the durability of freestanding tent poles over a long trek in Central Asia. Make your own choice here.

Tarp or “cowboy” camping is not a good option at higher altitudes. It’s too cold and too windy and you will need storm protection if you are in the mountains for long enough.

If you are planning on spending lots of time at high altitude or in the Eastern Pamirs, then you may want to consider a 4-season tent or a very sturdy 3-season tent. A winter climbing expedition tent is probably overkill (e.g., the expedition offerings from Northface, Rab, Mountain Hardware, etc.), and most of them are way too heavy to be carrying on your back for long hikes. Also, they do not handle moisture and condensation very well. So, I am leaning towards something sturdier and more trustworthy than an ultralight freestanding tent (examples that I consider too light and fragile: Big Agnes Copper Spur HV UL, NEMO Hornet OSMO Ultralight, MSR FreeLite).

So, for a long hike at high altitudes in Tajikistan across all terrain, I favor a freestanding tent with the following attributes:

Easy to pitch and secure in rough terrain and hard ground (therefore fully freestanding and not a partially freestanding or a trekking pole tent).

Can handle condensation (this rules out single-wall tents).

A tent that you trust in a high altitude storm (this disqualifies the lightest of the ultralight tents).

Not so heavy that you can’t carry it on your back for long treks with big altitude gains/losses (this will remove most famously storm-worthy tents from consideration - such as most of the Hilleberg tents).

Ignoring my own advice: I had a Durston X-Mid 1 trekking pole tent for four seasons (about 400 nights in the tent) and I purchased a new 2025 model. It’s way cheaper than high quality freestanding tents, and I feel I can salvage my tent after an exceptionally bad storm or if a curious cow inevitably tramples it (while a freestanding tent is more likely to be unrepairable). I’ve had four close encounters with bulls and calves over the last four years.

Sleeping bag: a bag with a temperature rating of 0 Celsius (30F) or higher is a risky move if you plan on camping at 3500 meters or above. Safest option is at least a -10 Celsius (14 Fahrenheit) bag, depending on if you are a warm or cold sleeper. Of course, this then makes for a bag that is too warm at lower altitudes.

Sleeping pad: Tajikistan destroys delicate things – lots of pointy stems/sticks, broken glass thanks to shepherds (veterinary medicines) and Russian climbers (vodka and cognac bottles), strange metal things left by unknown persons (1970s Soviet geologists?). The safest and most reliable option is a closed-cell foam pad instead of an inflatable air mattress. But note that nice flat soft spots are rare, so you may spend more than the occasional night on a bumpy, rocky surface with just a thin foam pad. If you bring an inflatable pad that is ultralight, consider bringing a thin closed cell foam pad to put below it as protection (and bring a tent footprint as further protection). I also check the ground before I put down my tent (sharp plant stems, glass, metal scraps, sharp rocks, etc.)

Consider also how cold a closed cell foam mat is. Check out the “R-Value“ of your mat to see its warmth rating. For example, in 2022 I used a Nemo Switchback. This closed cell foam sleeping pad is 415 grams and provides an R-Value of 2.0. In comparison, a popular inflatable air mattress, the Thermarest NeoAir XTherm, is 440 grams and provides a very warm R-Value of 7.3. However, R-Value should not be compared between closed-cell foam and inflatable pads - only within the same category - compare inflatable pads to inflatable pads, and closed cell foam pads to closed cell foam pads. The industry standard test is flawed, and closed cell foam R-Values are higher than advertised, or inflatable pad R-Values are lower than advertised, or a little bit of both. This video explains it.

What works for me: After the 2022 hiking season in Tajikistan I found that I had problems sleeping, and that possibly my thin and cold closed cell foam pad was to blame. So in 2023 I brought a thick inflatable pad. But I made sure it had a reinforced bottom side. For comparison, I used a Thermarest NeoAir XTherm that has 70D rated nylon bottom fabric. The Thermarest ultralight options — the XLight and the UberLight — have nylon bottom fabric ratings of 30D and 15D. My tent floor fabric is 20D polyester and the groundsheet below that is 20D polyester. That gave me a total of 110D. Some ultralight hikers’ inflatable pad set-ups hover between 40D and as low as 20D. I think that sort of thinness is way to risky (and cold) for Tajikistan. In 2024 I hiked from Mexico to Canada using two closed-cell foam pads stacked. I think I’m OK for comfort now, so this is now my set-up for 2025 in Central Asia. This has the benefit of being worry-free for punctures and leaks. But you may prioritize comfort and go with the inflatable option. If so, don’t forget your puncture repair kit (enough for multiple punctures).

Backpack

Due to lack of re-supply options on the trail and at trailheads, you will need to be carrying far more weight than you are used to. Consider that you won’t be able to resupply on food in most mountain villages – this is not California or Switzerland. The safe option is to carry all the possible food you may need, so factor that into your backpack size and its maximum carry weight.

In addition, I sometimes carry an ice axe, mountaineering crampons, river crossing shoes, town clothes, a large battery pack, and cold weather gear.

You will not do well with a 40-50 liter ultralight frameless backpack without load lifters on a longer trip in Tajikistan. Look into larger volume framed bags with load lifters that are rated for heavier gear carries, and make sure your backpack is sized to fit your torso (a pack with an adjustable torso length is a good option). Tajikistan is not the place for you to experiment with an unproven backpack while carrying heavy weights. Do test carries/hikes ahead of time.

If you are doing very long sections with a full range of extra gear (10+ days with crampns, ice ax, batteries, cold weather gear, etc.), then maybe look into larger backpacks designed for heavy carries or load-hauling. Examples: Seek Outside Divide, Mystery Ranch Terraframe, SWD Long Haul, Osprey Aether, KUIU PRO Divide, Deuter Aircontact Pro, Fjällräven Kajka, Arc’teryx Bora, Gregory Baltoro, etc. Those are all fairly expensive, but there are other cheaper options such as those offered by REI and Decathlon, etc. This is a North American-centric list. You may have additional options in your country that are suitable.

Some ultralight companies are realizing that hikers are overloading their bags, and have started to offer backpack models that try to compromise between weight of the bag and maximum carrying loads. An example here is the Durston Kakwa 55. This isn’t the bag for trip of 14 days that includes crampons and an ice axe, but you could probably use this bag on a sub 10-day trip in an area that doesn’t require ice axe, crampons and heavier cold-weather gear.

Mountaineering-specific backpacks are designed to deal with abrasion and snow. This makes them heavy and limits the external features.

Footwear and foot health

Specialized foot care instructions can be found in many places online if you aren’t already familiar with the challenges of long distance thru-hikes and off-trail trekking. There are just a few comments to be made on the particular conditions in Tajikistan that will affect your feet.

Consider that it is far easier to keep your feet dry in Tajikistan (unless you show up in early summer and insist in walking on the snow up high in boots/shoes with minimal waterproofing). The ground is usually dry as it drains well (mud is rare), August and September see little rain, you won’t be walking through dew-covered vegetation often, etc… Certain high valleys in the eastern Pamirs are an exception, as some of them have broad swampy bottoms.

The unrelenting steepness and rough trails (plus a heavier bag) call for special care to be taken in preventing blisters. American national park trails and European trails are practically flat sidewalks compared to trails/routes in Tajikistan. Open terrain high routes are the closest comparison to many trails in Tajikistan. Consider all possible options: sock + liner sock combo, Injinji style toe socks, anti-blister/chafe ointment, trekking poles (see below), a leukotape kit, etc…

If your route has many stream and river crossings, then an extra set of footwear (lightweight shoes or sandals) for river/stream crossing are a good idea (sharp rocks, difficult footing, keep your primary footwear dry). Plus, they are nice to wear at camp. If you are an ultralight hiker that walks through water crossings in your shoes and then counts on drying them off as you walk, consider the colder temperatures up high (cold feet, shoes won’t dry), the trail dust in some locations (very, very dirty shoes and socks), and the very steep trails (the worst possible time to be slipping around inside your shoes with wet socks).

Shoes versus boots is a very personal decision for each person. But keep this in mind if you go ultralight and wear trail running or hiking shoes: most of the trails here are far rougher than you are accustomed to. And the rock on the steep trails are high abrasion. You will be going down long pitches of scree/gravel, you will move laterally on a steep slope with no flat trail, and rocky areas can be very, very rocky. I’m usually a shoe wearer, but I wear boots if my hikes are longer than 3 days and if there is much in the way of off-trail open terrain or a very long steep descent.

Some people have gotten away with shoes on their mountain travels here for shorter treks. On a longer trek a trail running shoe will eventually rip apart. And in some areas you shoe will be full of dust, sand, rocks, seeds, burrs, etc (and those flimsy gaiters you think will fix that will not always work in the conditions here). And at times boots can keep your feet warm - it’s possible for you to lose some toes to frostbite in some parts of the eastern Pamirs and on the highest passes in western Tajikistan. Finally, you will shred your ankle bone on rocks. It’s best to have higher tops. My first trekking season in Central Asia I used hiking shoes on open terrain routes and ended up with bloody ankles and deep scrapes.

What works for me: I’ve previously used lighter weight hiking boots of the type that use suede or nubuck leather combined with some synthetics, a Gortex waterproof inner, and a reinforced toe cap. I destroyed these boots (Scarpa and Asolo) in a single season (seams coming apart, toe cap coming apart from the boot, tread destroyed, etc.). So for 2023 I switched to a full-grain leather boot: the Zamberlan 1996 Vioz Lux GTX RR. This heavier boot did its job, but presented a different problem (aside from the added weight). At the end of 4 months the tread was mostly worn through, while the full-grain leather uppers were intact. What’s the point of a heavier full-grain upper part of the boot being perfectly intact if you’ve run out of tread? I have no interest in sending my boot to a cobbler to get new Vibram soles (it can be over $200 with shipping included where I live). For my next season I will wear a lighter boot where I think the tread and uppers will wear out at the same time: the lighter weight Zamberlan 1110 Baltoro Lite GTX RR.

I’m not telling you to get Zamberlan Baltoro boots, I’m just giving those as an example (they are my choice as Zamberlan has wide toe boxes which I need, and they are made in Italy, not outsourced to an Asian factory).

What works for others: I know of 4 people who have thru hiked the length of Tajikistan using trail runners - and all of them doing it in the later dry season (August-September). The risk here is fresh snowfall in eastern Tajikistan where you will be at high altitudes for long stretches. And note that all four of these people were very experienced long-distance hikers, so they had good idea of what their feet could handle.

Trekking poles: I’ve done most of my hiking at home without them, but there are some long steep downhills in Tajikistan that aren’t nice sculpted zig-zags/switchbacks like in Nepal or Europe or California. Poles have definitely saved me from slipping and falling here. Poles will help your feet and knees, especially considering that you will be carrying a heavy load. They also scare the sheep dogs, who don’t know that an aluminum or carbon fibre pole can’t possibly hurt them.

General health + Water

Make your own medical kit, as the options for sale are not very good (or way too heavy). I suggest referring to Andrew Skurka’s medical, foot care and gear repair kits list.

Insects are rarely a problem. The exception are the mosquitoes in some forested or swampy areas next to some of the mid-elevation lakes in the warmest part of summer. But these areas are very few. Occasionally sheep flocks are followed by horseflies, and shepherd camps usually have plenty of non-biting but annoying flies. However, this is not Alaska or Greenland or northern Canada, so I carry only some repellent wipes (and I’ve never used them), not a large bottle of repellent. Plus, I have a bug net that goes over my head (and weighs almost nothing). What are an issue are fleas (at some shepherd camps and summer villages, or on dogs) and, rarely, bedbugs in some people’s houses or in cheap hotels (but only in lower altitude areas as far as the anecdotes show).

I know of no crawling biting insects (e.g., ticks) up high in trekking areas. Ticks, however, may be waiting at lower elevations. If you are paranoid, then you can do what I do. I have a sun hoody, socks, a neck gaiter and trekking pants that are all permethrin-treated. You can search online for clothing with this (safe and odorless) insect repellent treatment, or you can send in your preferred clothes to be professional treated by a US-based company, Insect Shield (they serve every country but Canada, so Canadians will need to buy pre-treated clothing).

Water: The mountains of Tajikistan are not the tropics or some heavily urban or industrial area, and you can often find good, clean springs and pristine high elevation streams. But there are shepherd camps, livestock and dogs throughout the mountains, so you need to treat or filter your water, especially when you are below the highest shepherd camp or on a shepherd route. Your options, from lightest to heaviest: chemical treatment, UV treatment, filter, purifier.

Drawbacks of each: most chemical treatments kill viruses and most pathogens/bacteria, but they don’t get cryptosporidium. A few do, but they require up to 4 hours to kill the crypto. And Tajikistan has cryptosporidium. UV requires a battery operated electric device, and it only works in very clear water. The type of UV filter that kills crypto is a large household filter, not the little lightweight stick that trekkers carry. Filters can be slow and work-intensive and many will eventually get clogged/destroyed by silty water (very common with so many glacier streams in Tajikistan), and filters do not get the small viruses, only the large pathogens (but viruses are not much of a problem in the high mountains). Purifiers get everything, including the viruses (plus chemicals and trace amounts of heavy metals), but they also clog quickly in silty water, plus they are heavier (with filters that don’t last that long).

How about boiling water? You have to bring to a full boil and then wait for a few more minutes. This uses a lot of fuel (with gas and firewood being difficult to come by in many parts of Tajikistan).

My system? I carry a filter for clear water (Sawyer Squeeze, Platypus QuickDraw, or HydroBlu Versaflow) that filters the bacteria/pathogens. I then add some quick 30-minute chemical treatment pills/drops for viruses if the stream is below a shepherd camp or village or popular trekking area. For silty water I use a chemical treatment (Katadyn Micropur MP1) that is effective against cryptosporidium after 4 hours (unless I’m right below a glacier, then I just drink the silty water straight). I don’t filter or treat spring water or even some of the highest snow melt/glacier water.

How much water will you need to carry? I’ve rarely needed to carry more than 3 liters in the mountains, but some areas with few water sources may require you to carry more. In some areas I never need more than a single 1-liter bottle.

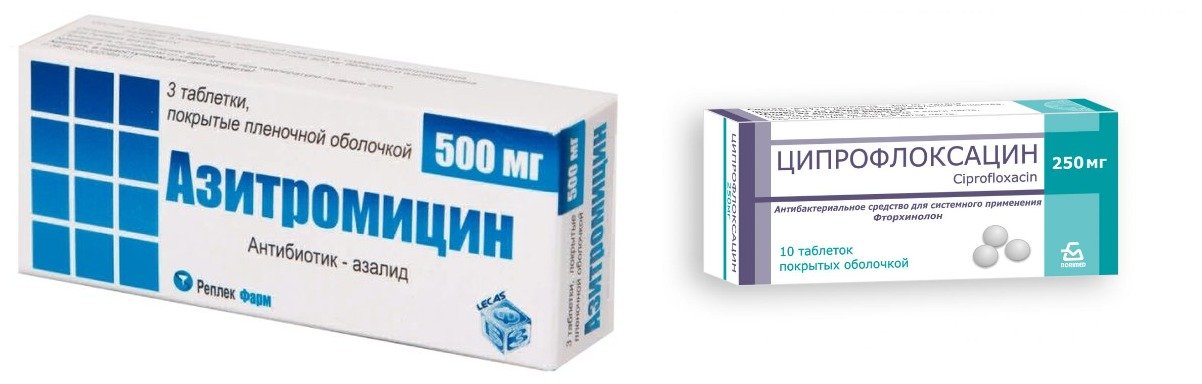

What if you do get sick anyways, whether from water or food? I carry two different types of antibiotics: ciprofloxacin (ципрофлоксацин) and azithromycin (азитромицин). I buy them in Tajikistan from pharmacies where they are available over-the-counter (i.e., no doctor’s prescription/script required) for a very low cost (IIRC, $2 for the ciprofloxacin and $5 for the azithromycin). These do nothing against viruses, but this is a mountain cold water environment, not the jungle or a populated area – viruses are not so much of a consideration. I use the more mild ciprofloxacin first before resorting to the stronger azithromycin.

Show these images below to a pharmacist in Tajikistan:

I have never gotten sick while hiking in Tajikistan (since 2012), and that includes getting invited for meals at shepherd camps. The biggest danger in Tajikistan are roadside cafes and street food (plus certain fruits and vegetables).

2022 update: I got sick in the mountains. I don’t know if it was the guesthouse I had been at 24 hours earlier, the sausages/cheese that were in my hot backpack for 48 hours, the dried fruit I was given by villagers, or carelessness while filtering water. For two days I had an upset stomach and no appetite, plus general weakness. Very mild in comparison to what has happened to some travelers in the cities and towns.

2023 update: I had an 8-hour long stomach illness. I had to stop and lay next to a river in total misery for about 4 hours when I was at my worst and could no longer walk. The cause? For two days I had a pack of hotdogs that require refrigeration, I had yoghurt, tea and bread at a shepherd camp, and for whatever reason I drank filtered stream water (in a livestock area) right after I had accidentally put the filter on backwards and contaminated it. So I’m not sure… But that’s 8 hours of illness over 5 months of hiking in Central Asia in 2023.

Electrolyte crashing: it can be hot, and you will sweat a lot at lower and mid-elevations. Carry flavored electrolyte powder to put in your water or bring pills to chew. I also bring electrolytes because of the difficulties in finding healthy food regularly in the mountains. My hiking diet is not at all balanced so electrolytes and multivitamins are a good idea. With a good diet you don’t need these supplements.

Sunburn: SPF 40-50 sunblock cream is a good idea. It is very sunny in Tajikistan and you will burn in the mountains easily. A better idea than sunblock/sunscreen lotion/cream are pants, long-sleeve shirts or a sun hoody, sun gloves, and covering your neck/face with some combination of either a hood, an ultralight neck gaiter, a hat, sun-flaps, etc… I use the sunblock clothing option, with just a tiny amount of sunblock cream/lotion for the small part of my face that isn’t covered. This is a personal decision, and some people prefer the cream/lotion, while I prefer the clothing. I do this to save weight on a bottle of sunscreen that needs to be reapplied several times per day, and because many trails kick up a lot of dust that will stick to your sunscreen and leave you a dirty and greasy mess.

And for a neck gaiter, try one of the lightweight, breathable neck gaiter options from Buff. Google will direct you towards sun gloves that are suitable for hiking (get one with a reinforced palm if you use trekking poles). Take note that the companies that focus on hikers and climbers sell expensive sun protection clothing (with some models so lightweight as to be not very durable), while companies focused on sports fishing and construction workers sell much cheaper sun protection clothing (e.g., Bassdash).

For a sun shirt/hoodie, do your research to find what works for you. For example, for a sun hoodie I want a UPF 30-50 sun protection factor, antimicrobial treatment to prevent odor, and durable fabric for the all the abuse (branches, leaning against rocks, scrambling, 4 months of daily use, etc…). This results in a hoodie with fabric that is not as comfortable or breathable as the lighter options. But another person may prioritize a more comfortable/breathable fabric and choose a different sun hoody (but probably sacrifice durability or sun protection levels). As for gloves, I favor a reinforced palm for long-term trekking pole use (and some scrambling on rocks), so I lean towards Glacier Glove’s Ascension Bay Sun Gloves or the Bassdash brand fishing gloves with a reinforced palm. For a neck gaiter I wanted an insect repellent-treated fabric, UPF 50 sun protection, odor-control technology and a fabric light enough for the warmest days. This led me to Buff’s Coolnet UV Insect Shield model.

Dry skin: This is more so of a problem in the Pamir mountains. During a month-long trekking trip in the Pamirs in 2023 my hands and face were very dry, and I desperately wished for moisturizing cream. It was very, very uncomfortable. And there was some skin cracking on my thumbs. Next time I do such a long trip I will bring a moisturizer (enough for my face and hands). The western parts of Tajikistan are not so dry, but I would still bring a small amount.

The stinging/burning yughan plant: see our long article on this seasonal plant (a bigger problem in the early season). If you are only going to the eastern Pamirs or on the popular Fann Mountain routes, then you don’t need to worry as much about yughan.

Deodorant and body odor: dispose of any American ultralight thru-hiker ideas about leaving the underarm deodorant at home. You stink, and it’s not acceptable go into people’s homes or cars while you stink. This is not the Appalachian Trail. While in mid-hike (homestays) and at the end of your trek (transportation) you will need to not stink. Want to save weight? Carry travel-size deodorant, or buy a regular size deodorant stick and cut or break off a piece of the deodorant and stick it in a small plastic bag. And wash whenever you have the opportunity. Locals don’t get into a car or go into someone’s house when they are dirty and smelly, and neither should you.

Example: I shared a car ride with 3 mountain shepherds who were returning home for a break. I came from a mountain guesthouse where I had a shower and put on a clean t-shirt, while they washed up in a river and took out a special set of clean clothes they have for when they leave the mountains. When I don’t have the chance to go to a guest house before finding transportation, I find a river or stream where I can wash one of my shirts (or put on a fresh shirt), wash my hair and face with soap, and reapply deodorant.

Toilet: if you want to go fully ‘Leave No Trace,’ then bring a trowel so you can bury your waste. And go far from the trail, far from any camping area and from any water source. Note that in the bigger supermarkets in Tajikistan they sell wet-wipes, but they are all some sort of thin, low quality synthetic mix-blend wipes, not high quality biodegradable thick paper wipes. Regular toilet paper is far more friendly to the environment than the synthetic wipes. My system is to buy the high quality biodegradable wipes at home, remove them from their plastic bag/dispenser, dry them out (to save weight), and then repack them into a ziploc bag to be “rehydrated“ on the trail.

An increasingly popular tool are the various ‘bidet’ attachments you can put on any old plastic Coke bottle (a bottle you don’t drink from, I favor a 700ml bottle). These weigh barely anything, and they deliver a directed cleaning stream of water to where you need it (1. spray clean, 2. wash with soap, 3. spray again to clean off soap, 4. wash hands). This leaves you far cleaner and you use far less toilet paper or wet wipes – or none at all for some people. Google this: water bottle bidet. Note that this system is something a local will consider normal, as they do the washing technique here (note the water jugs with a spout outside of the pay-toilets, mosque toilets/washing areas and in people’s toilets outside their homes).

If things get out of control (diarrhea), then the bidet tool will be particularly useful. And don’t forget the Imodium (loperamide anti-diarrheal) medication to slow or stop the diarrhea. Maybe also bring a small amount of something like “Preparation-H” (US/Canada brand) or any sort of hemorrhoid cream or ointment (these are not just for hemorrhoids, they all have multiple ingredients for a variety of symptoms that will make you far more comfortable). The only specific Tajikistan-related advice is regarding the tendency of tourists to buy a large amount of dried fruit from the bazaar or gorge themselves on fresh fruit and berries. Spend a few days eating regular large servings of fruit as a test – you will be using the toilet quite often and in unexpected and unwelcome ways.

Follow all the advice above to avoid an inflamed, itchy, painful chaffed and generally unhygienic and unhealthy anal region.

In 2023 I discovered that, for the first time in 40+ years of hiking, I needed a laxative. I had never used them before, and I had no idea why a healthy person would need them. But you will, like I did, be carrying one-two weeks worth of food, depending on your route, and your diet will be different than at anytime before in your life. And this includes previous thru-hikes, as the options for resupply here in Tajikistan are not very good. In 2023 I was eating lots of peanut butter, Snickers, tortilla bread, dried fruit, salami and nuts, as this is what was available in Dushanbe supermarkets. I’m not sure what was to blame, but I ended up with bad constipation for the first time in my life. When I returned to the city, I immediately went to a pharmacy and bought some laxative pills. They came in useful a couple of weeks later when I again had the same problem… In 2024 I will have them in my medical kit ahead of time.

There are no toilets in the mountains, but shepherds do sometimes dig temporary drop-holes near their camps. And – western Europeans take note – if you come across a rock wall (single, double, triple or one round circle) with a nice flat space behind it, this is not a toilet or a privacy wall. This is a windbreak tent spot built by Russian mountain climbers/trekkers or by the local shepherds, or it’s a seldom-used rock corral for livestock. It is not a toilet. Somehow tourists have started to use these as toilets in the Fann Mountains, much to the confusion of the local people and the Russian climbers.

Consider also that a rock wall may be the ruins of an old home foundation, and the site of Soviet-era genocide and ethnic cleansing – a common occurrence throughout the mountains of Tajikistan (from the 1930s through the early 1970s). Using these places as a toilet is obviously not appropriate.

Another bad habit is practiced by most western tourists – being scared of the dark and therefore going to the toilet at the camp, rather than putting on a head lamp and walking to an area farther from the camp. There are no predators that will eat you in the dark (exception: eastern Pamirs in wintertime when the wolves are really hungry). In high season in the Fann Mountains you need to be careful to not step in human feces next to some popular lakes.

Clothing

Many general guides to 3-season appropriate hiking clothing exist online. Andrew Skurka’s is very clear and concise.

Special clothing considerations for Tajikistan’s mountains (from the perspective of people who are used to the Alps, Rockies or a similar climate region) are mostly related to low and mid-elevations where it can get hot. So I have multiple lightweight layers that I can adjust according to the conditions (a t-shirt, a sun hoody, a lightweight synthetic long sleeve button-up shirt, a lightweight alpine fleece hoody, a puffy/synthetic jacket, and a rain jacket/shell). A heavy wool or thick synthetic shirt will make you miserable in the heat (but should be quite fine for the highest elevations and the colder eastern Pamirs).

Hypothermia: For keeping hypothermia away, just follow the general clothing guide that is linked above. But then consider that you may actually have some persistent winter conditions on certain high elevation treks, even in August. Do your research, and be safe: bring clothing that will let you survive below 0 degrees Celsius in wind and snow (at least for brief periods). A trip to high passes in the eastern Pamirs probably calls for an extra layer of clothing. It can get very cold and windy here. Some of the passes will require a winter-gear set-up if the weather turns bad. If you are trekking anywhere east of the Bartang valley, be ready for surprise August winter weather that you can’t easily escape from.

Sun protection clothing: for those who don’t like carrying and reapplying sunblock cream, there are good clothing options. I use a sun hoody with a high UPF protection factor when it’s warmer at lower and mid-elevations, and some people use a “sun shirt” (just a lightweight breathable shirt with a good UPF sun protection factor). Like mentioned above, you can then combine this with ultralight sun gloves, a neck gaiter and a hat.

Rain gear: For rain, you really do need both a rain jacket and rain pants. The eastern Pamirs are quite dry, and in August/September western Tajikistan has low rainfall. But isolated rainstorms can happen at any time. I have rarely encountered rain in the later summer, but my rain pants are not wasted. They serve as a wind break layer when I’m up high in cold and windy conditions. And they are an extra layer that I can wear at camp when it’s cold.

For your rain jacket you can go with ultralight options in the Fann Mountains and on the most popular routes in the Pamirs, as you will rarely be in terrain where trees/brush may rip or poke holes in a lightweight jacket (with some exceptions). I also carry rain mitts that go over my gloves – these can also be useful as a windbreak layer in very cold and windy conditions. Homestays and guesthouses are few and far between in Tajikistan, so don’t count on being able to dry your clothing overnight.

Note added after summer 2022: The summer weather was very different from previous years/decades. Isolated heavy rain storms made regular appearances throughout the summer, as opposed to the usual dry season. It’s unknown if this is a single aberration, or the new climate-change normal.

Summer 2023: More bizarre weather. A late August storm dumped monsoon-levels of rain in the mountains. I was lucky to be on a break in Dushanbe. Being caught in that storm at altitude would have been very dangerous.

2024: back to normal weather patterns.

Stinky clothes: Merino wool is good for resisting odor, but for some people it is too expensive, itchy or hot – and merino is weak and not as durable as synthetics. I use synthetic shirts and hoodies that have some sort of anti-microbial odor control technology. I have gone through five shirts from five different brands and all of them work. I also have a sun hoody and a long underwear base layer that offers the same odor control.

Wear pants, not shorts. This applies to both men and women. In most of Tajikistan, shorts are highly inappropriate to wear in a village or at camp, and almost everywhere in Tajikistan you should definitely not wear shorts in people’s homes. This is changing in regards to local tourists from the cities who disregard rural culture, and some parts of Tajikistan have more loose standards for covering your body. Beyond cultural reasons, the stinging yughan plant will destroy your vacation with a single brush, some areas have thistles, other areas have low brush that will scratch you, a few locations have biting insects, and with pants you won’t need to be constantly applying sun block cream to your legs. As for your upper body, wear clothing that covers down to your elbows.

Clothing durability: Sitting on rocks, rubbing against rocks, tree branches and bushes grabbing or rubbing against your clothing, sliding/falling on steep gravel routes, thistles and other rough conditions can be expected on many of the longer routes in Tajikistan. This is not the place for thin, ultralight material designed for desert/jungle travel. These type of pants are amazing for short trips in good conditions, but if you want clothing that will last for a month or more in adverse conditions, buy clothing that is more durable.

What works for me: I started out wearing heavier, more durable (therefore hotter) pants. But the result was some overheating at the warmer lower elevations. Find what works for you, but you may need to compromise. I ended up somewhere in the middle and I use two different pants: Eddie Bauer Guide Pro (~320 grams) and Patagonia Quandry (~285 grams). Compare these to the heavier weight more durable pants ideal for colder conditions: Rab Incline AS Softshell Pants (420 grams), Decathlon Forclaz Mountain Hiking Pants (410 grams), Arc’teryx Beta AR Pants (470 grams), or ultra durable pants like Montane Super Terra Pants (up to 720 grams), etc...

Cooking and Food

Gas: You can’t fly with camping gas in your baggage. Cooking/camping gas canisters are only regularly available in Dushanbe, and a visit by a large Russian climbing team can result in all stock being sold out. And you can’t reliably resupply anywhere, unlike in Europe and on popular American trails. If you are on a long, extended trek, then you will be risking having no way to cook your food.

An option here is a “universal fuel” burner. These can use petrol/gasoline, diesel, kerosene and other types of fuel that you can actually buy in the bigger villages in Tajikistan. A popular model is the MSR WhisperLite. Read reviews of these sorts of stove. I tried it, and I ended with my hands covered in stinky fuel and carrying too much fuel and dealing with a flame that was too strong and that left lots of carbon residue (soot). But some people do find them useful, and have mastered them in a way I was not able to.

Firewood? Don’t count on it. The eastern Pamirs have almost no trees or bushes, especially not next to a trail, and above a certain altitude throughout Tajikistan there is either only grass or no vegetation at all. Elsewhere has little to no forest cover. Environmental concerns include Tajikistan’s terrible rate of deforestation. As for social issues, local people and shepherds need that firewood you burn.

The lightweight, most reliable and environmentally-friendly option? Cold-soaking or eating only ready-to-eat food like salami, crackers, bread, nuts, dried fruit, chocolate, cold cereal, etc… Read this article as an introduction to the sad world of cold soaking, and this article for recipes. The downside is that you are eating cold food and starting your day not with hot coffee/tea, but rather with cold water (or cold coffee in my case), and ending your day with a cold meal.

Food options in Tajikistan: Supermarkets in the bigger cities and towns have the usual options, but minus any special trekking food such as dehydrated meals. Villages can be risky, with small villages either having no grocery store, or having a small shop that sells only snacks and candy. The people in these small villages rely on buying bulk food (flour, rice, pasta, sugar, oil) from bigger towns/cities and sourcing the rest from their own gardens/fields and livestock (potatoes, fruit/nuts, dairy products, meat).

You may need to carry a lot of food. There are some treks that can take up to two weeks and don’t go through a single village. You will need to consider that the weight of your bag will be quite heavy with so much food.

If the food you carry is not so healthy (ramen noodles and chocolate bars), then consider bringing multivitamin/mineral pills or powder.

Bread note: bread may be omnipresent in Tajikistan, but it’s usually not available for sale in the smallest villages. People buy flour and other ingredients in bulk and bake their own bread. They don’t buy it from a store. Don’t expect bread to be for sale in these small food stores.

When you do manage to get bread, know that it does not have preservatives like the bread you buy at western supermarkets. Without the calcium propionate preservative, for example, mold flourishes. When your put bread into a plastic bag and then inside your backpack, you are creating a perfect environment for mold: warm and moisture sealed in. I’ve lost 5-days worth of bread to fast-growing mold overnight. I now put the bread in a very breathable mesh bag and, if weather allows it, it goes in an open pocket outside of the main compartment of my backpack. I intentionally dry out the bread. Dry bread is edible, moldy bread is not. Thanks to the shepherds for showing me the errors of my ways.

Gear Extras

Crampons and Ice axes?

Yes. Depending on the route and the time of year and the level of snowfall that year. But you can select a route or time of season where you don’t need crampons or an ice ax. Research is required.

Satellite Communication and Rescue Devices

Once you go above the last of the grass, you will no longer see any more shepherds (except for a couple of high passes that are used by shepherds as resupply or access routes). Most routes see little to no tourists. If you get hurt and need help, or even if you just want to provide progress updates, you need a satellite phone or a satellite SMS/text device. The Russian climbers usually bring a rented satellite phone with them, but trekkers - if they have a satellite device - generally have a cheaper satellite SMS device that can send and receive text messages (with your GPS location included), as well as send an emergency distress message with the press of a button.

As of 2025, your choices of brand for satellite texting, location update and PLB devices with full global coverage are Garmin InReach, Zoleo, ACR Bivy Stick, and Iridium Go. Googling these brands will lead you to some review articles (some of which make detailed comparisons). I chose mine based on the flexibility and price of the service plans, while other buyers seemed to not prioritize the price of the device or the monthly plans, but rather the weight of the device. Choose what works for you.

Note that some of the devices have no screen or keyboard and need to be paired/tethered with your smartphone, from where you can send and receive messages on a special app, but the device itself does have an emergency SOS button and/or a “check-in“ button that will send an automated “I’m OK“ message along with the coordinates of your location.

Yes, the emergency button does work in Tajikistan (just check to make sure the company selling you the service has global coverage). Multiple groups have been rescued after hitting their SOS button.

Navigation and Maps

Dedicated GPS navigation devices are quickly disappearing and having offline maps on smartphones taking their place. For maps and apps, check out our detailed guide. If you don’t want to read that in-depth advice, you need to at least know that many map apps that work well in North America and Europe are not helpful at all in Tajikistan. You need the OsmAnd map app (still the best choice as of 2025), with the Mapy.cz map app being second best.

Batteries and Power

As of 2025, solar power panels are still not a great choice in terms of weight, bulk, fragility and charging power (especially for someone on the move during the day). An external rechargeable battery power bank is the best choice. A 20,000mah power bank is a good choice for trip of up to one week (for a person who uses GPS often and who takes many photos and video). A person who does not often need to look at GPS navigation or take many photos/videos may need less battery. Make sure to go with a good reliable brand (e.g., Anker). In 2022 I had a new phone that was more battery-efficient than the much older phone I had previously owned. I did one 10-day trip with intensive battery use: video, photos, map editing, GPS track recording, navigation, shepherds looking at my camera roll, etc… At the end I still had enough in my 20,000mah power bank to go for another couple of days.

Special battery considerations for hiking in Central Asia

Rural areas can have electricity rationing, outages or shortages. Guesthouses may have a single electric outlet for multiple guests. A guesthouse in an isolated area may run an electric generator for only a few hours in the evening. You may want to watch your power bank while it charges in the hostel or guesthouse as for some reason foreign tourists and guesthouse family members here do steal on the rare occasion. There are long distances on the trail. For these reasons, you need certain specification for your power bank, charger and cords.

You will need lots of spare battery capacity - a 20,000mAh power bank at a minimum. The high route has a 160km section between battery charging points (guesthouses). If you are a heavy user (video, photography, music, reading, internet, etc.), then bring more. To play it safe, two 10,000mAh power banks are safer than one single 20,000mAh power bank, and two 20,000mAh better than one 40,0000mAh (your could drop it in a river, it could die on its own, it could get fried by a power surge, it could get stolen while charging, etc…). If it gets close to freezing, sleep with the power banks (and your phone) inside your sleeping bag. And a sealable plastic bag or dry bag is good for protecting your batteries and electronics if you get wet from rain or a river crossing. As for quality, the Anker brand is very consistent.

Make sure your power bank supports 30W charging. And I don’t mean that the battery pack outputs 30W to your phone or other electronics, I mean that 30W is going to your power bank from the 30W charger. This takes some investigating, as manufacturers and sellers focus on telling you how quickly your battery charges your devices with how many watts (W), or “output,” but they often hide or don’t mention the info on how many watts their battery can “input” from a charger (important info for a hiker with limited time to charge their battery, and who may be competing with other tourists for limited electric outlets).

And bring a 30W charger. A regular charger (usually 5-10W) will take ~20 hours to charge a 20,000mAh power bank. You need a Euro plug, not North American plugs (you can buy an Anker Nano 30W charger with European plugs from Amazon Germany or any European seller who delivers to the US/Canada/Australia etc.). You could just use a travel adaptor, but that’s adding a low quality item that can fail (or, like I’ve experienced, slip loose at an angle and stop charging). You should also have a 30W PD USB-C to USB-C cable so that your battery pack will actually charge fully overnight (the longer the cable, the better, some electric outlets are unreasonably high on the walls in this region). And an extra cable is always a good idea.

Do you just want a recommendation for a set-up? Sure, here you go:

Anker 537 Power Bank (24,000mAh)

Anker Nano 30W charger (European plugs)

Anker 643 USB-C to USB-C Cable

According to the manufacturer, this set-up above will allow you to recharge a dead 24,000mAh battery in 3.5 hours. Note that sellers sometimes don’t mention the Anker model number (537, 643, etc.) so you may need to compare specs from the Anker website to whoever you are buying from (if not buying directly from Anker). If you want to take my advice from farther above and combine two smaller power banks, then get two Anker Nano Power Banks (10,000mAh each) that support 30W charging.

Can you go higher than 30W? Sure. Look at power banks targeted towards laptop users. Generally you will see 65W charging input being advertised for that. Anker claims their 65W charger will fully recharge a 25,600mAh power bank (the “747” model in 2.5 hours). The main consideration for this is that the 65W charger will be significantly heavier (almost 4x) and bulkier if you are counting grams and ounces in your bag.

Liquids, gels and creams: I use small travel-sized containers to carry shampoo, soap, and assorted medicines (anti-inflammatory, anti-fungal and and other liquid or cream medicines). Make sure to buy high quality containers. I bought a cheap set from Amazon and some of them exploded/leaked when I gained altitude (due to the pressure differences). A good tactic is to squeeze out the excess air from the containers/tubes so that the contents have room to expand. It won’t just be hiking, this can happen when you drive over some of the high passes, especially in the eastern Pamirs. You can also align the containers inside your bag so that the tops of the containers face up, not down (so that air gets squeezed out, not liquid). Also, after gaining elevation I check my containers to see if I need to release pressure.

Final note: At some point in time I have ignored almost every single piece of advice listed above. I’m still alive and healthy, but ignoring the above advice does carry a level of risk or discomfort.

For other types of advice (animals, dangers, local social norms, etc..) read this general advice.